Shangri-la is best-known as a fictional place—an idyllic valley first imagined by a British novelist in the 1930s—but look at a map and you’ll find it. Sitting at the foot of the Himalayas in southwestern China, Shangri-la went by a more prosaic name until 2001, when the city was rebranded by Chinese officials eager to boost tourism. Their ploy worked.

The star of Shangri-la is the Ganden Sumtseling Monastery. Since its destruction in 1966, during Mao’s Cultural Revolution, this Tibetan Buddhist monastery has been rebuilt into a sprawling complex crowned by golden rooftops and home to more than 700 monks. It was humming with construction when I visited in October—and filled with Chinese tourists.

Like many monasteries, Sumtseling is thriving thanks to Tibetan Buddhism’s growing popularity in China. When the government loosened restrictions on religious worship in the 1990s, the practice took off, especially among urban elites unsatisfied with the Chinese Communist Party’s materialist worldview. It’s an open secret that even high-ranking party officials follow Tibetan lamas.

Tibetan Buddhism’s recent spread presents both a threat and an opportunity for President Xi Jinping. He wants to make China politically and culturally homogenous, a goal that could be jeopardized by a tradition steeped in Tibetan language and history. But Xi is enacting a program that seeks to turn the rising popularity of Tibetan Buddhism to his advantage—to transform the tradition from a hotbed of dissent into an instrument of assimilation and party propaganda. If it works, it could smooth his path to lifelong power and help him remake China according to his nationalist vision.

Tibetan Buddhism isn’t only a spiritual practice; it’s an expression of Tibet’s cultural identity and resistance to Chinese rule. The CCP annexed Tibet in 1951, claiming that the then-independent country belonged to historical China and had to be liberated from the Dalai Lama’s Buddhist theocracy. The Dalai Lama fled to India to establish a Tibetan government-in-exile, and Tibet has been a source of opposition to Beijing ever since.

According to the Tibetan scholar Dhondup Rekjong, Xi’s ultimate goal is to erase Tibet’s language and cultural identity entirely. In a campaign similar to the CCP’s oppression of China’s Uyghur Muslims, Tibetan teachers and writers have been arrested as “separatists” for promoting the Tibetan language, and more than 1 million Tibetan children have been sent to boarding schools to be assimilated into Chinese culture. Xi’s effort to control Tibetan Buddhism is just one piece of this long-standing effort to suppress Tibetan identity, but it has taken on an additional valence as the practice expands in China.

To co-opt Tibetan Buddhism’s popularity, the CCP recruits religious leaders willing to implement what it calls Sinicized Buddhism—a combination of state-sanctioned religious teachings and socialist propaganda taught by party-approved clergy—and rewards their monasteries with money and status. The well-funded Sumtseling monastery, for example, has been officially designated by the CCP as a “forerunner in implementing the Sinification of Buddhism.” To detach Buddhism from Tibetan culture, monks are pressured to replace traditional Tibetan-language scriptures with Chinese translations. According to Rekjong, they will soon be expected to practice in Mandarin.

The approach is part of a broader campaign to influence all religions in China. As of January 1, every religious group is legally required to “carry out patriotic education and enhance the national awareness and patriotic sentiments of clergy and believers.” Failure to pledge loyalty to Xi, display the Chinese flag, and preach “patriotic sentiments” is now punishable by law. If Mao wanted to eliminate religion, Xi wants to nationalize it.

Co-opting Tibetan Buddhism will bring Xi one step closer to achieving what he and the CCP call the “Chinese dream,” a vision that seeks to unite China’s ethnic groups—its Han majority, Tibetans, Uyghurs, Mongolians, and dozens more—in their dedication to the motherland and party. Xi has already consolidated more political power than just about any other modern leader, but realizing the Chinese dream will require something arguably more difficult: winning the hearts and minds of his subjects. As communist ideology loses its allure, Xi is enlisting religion to sell his program to the people.

But it may not be that easy. Joshua Esler, a researcher who studies Tibetan culture at the Sheridan Institute of Higher Education, in Australia, told me that Tibetan Buddhism has grown so popular precisely because it offers the Chinese something their government can’t. Many Han Chinese, he said, “believe that Tibetan Buddhism has retained a spiritual authenticity that is lost in China.” They see Tibet as an alternative to the corruption, materialism, and environmental degradation that characterize life under the CCP. Any government interference in Tibetan Buddhism might alienate its followers, pushing them toward Buddhist leaders who secretly support the exiled Dalai Lama.

As for Tibetans themselves, Sinicized Buddhism is unlikely to become popular anytime soon. Many of them consider monasteries that have too eagerly embraced Xi’s program to be sellouts. But as the government ramps up its campaign—and as a new generation of assimilated Tibetans comes of age—that might begin to change.

After visiting Shangri-la, I went to the remote Tibetan town of Daocheng, where a young monk named Phuntsok showed me around his monastery. “Without the Communist Party, we would not have freedom of religion,” Phuntsok told me as we walked through ornate chapels. He extolled the CCP’s support for Tibetan Buddhism, and no wonder: Locals told me that the monastery, Yangteng Gonpa, had received substantial government funding. A freshly paved road snaked up the mountainside on which the monastery was perched, ending at a parking lot built to accommodate hundreds of visitors. A new welcome gate was being erected, and the tourism office promoted Yangteng as one of the area’s main attractions.

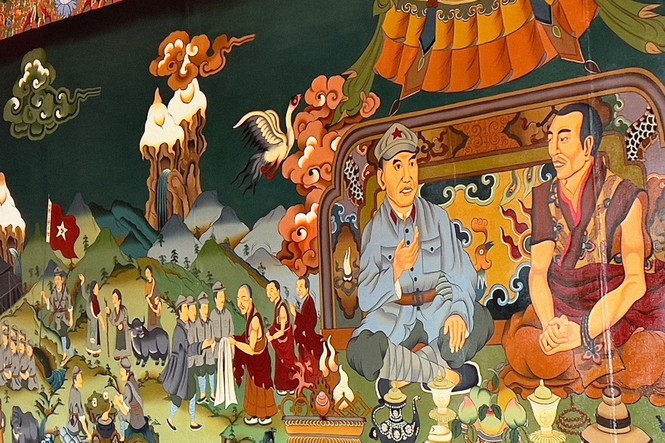

I followed Phuntsok up to the second floor of a chapel, where he showed me an exhibit celebrating the monastery’s “liberation” by the Red Army in 1950. The space doubled as a classroom; a whiteboard showed the faint outlines of a lesson on how monks can “actively guide religion to adapt to socialist society.” Though the monastery belongs to the Buddhist tradition of the Dalai Lama, Phuntsok didn’t mention the exiled spiritual leader, whose name and image are censored in Tibet.

Instead, Phuntsok praised Gyaltsen Norbu, a Buddhist leader who was handpicked by the CCP as a child to be the Panchen Lama, a position second only to the Dalai Lama. (Many Tibetans don’t recognize Norbu as legitimate; in 1995, the Dalai Lama identified another child as the Panchen Lama, whom Chinese authorities promptly detained, and whose whereabouts remain unknown.) When the 88-year-old Dalai Lama dies, Norbu will likely be tasked by the CCP to select his replacement, who will be raised under CCP supervision and expected to promote Sinicized Buddhism. Westerners tend to imagine the Dalai Lama as a force for peace and human rights, but the position can just as easily be put into the service of totalitarianism.

Gray Tuttle, a Tibetan-studies professor at Columbia University, told me that the CCP is wary of any religious movement that isn’t under its control. In 2017, the government issued orders to tear down Larung Gar, Tibet’s most popular Buddhist monastery. Thousands of residents, including many Han Chinese, were displaced from the remote valley where they had come to study. The official reason for the evictions was that the monastery didn’t comply with safety regulations; the likelier explanation is that, despite the government’s initial support for the monastery, the CCP felt threatened by its success and the influence of its teachers. “The CCP definitely wants to limit the charismatic power of any particular lama,” Tuttle told me.

The challenge Xi has set for himself, then, is to reshape Tibetan Buddhism without undermining its allure. Judging by the large crowds at Sumtseling, he’s succeeding—at least among some Han Chinese. “Tibetan lamas possess the deepest knowledge,” a Han woman named Jin Yi, who had traveled 400 miles to the monastery to meet her guru, told me. But devotees like her were considerably outnumbered by tourists, many of them dressed up as Tibetan pilgrims and modeling for photos—striking lotus poses, spinning prayer wheels, or staring in feigned rapture at Buddhist murals. Few entered the chapels, where photography was prohibited. Government-sponsored monasteries like Sumtseling might attract tourists looking for a photo op, but lavish temples won’t win over true believers.